The earliest pieces were made by pressing the clay into shape. This method continued to be employed after the invention of the wheel, such as when producing Rengetsu ware. Coiled methods developed in the Jōmon period. Production by kneading and cutting slabs developed later, for example, for Jamie’s clay figures .

Potter's wheel

The first use of the potter's wheel in Japan can be seen in Sue pottery While Sue productions combined wheel and coiling techniques, the lead - glazed earthern ware made under Chinese influence from the 8th to the 10th centuries include forms made entirely on the potter's wheel.

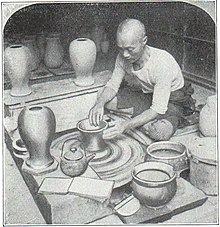

The original potter wheels of the Orient was a circular pad of woven matting that the potter turned by hand and wheel, and was known in Japan as the rokuro. But with the arrival of the te-rokuro or handwheel, the mechanics of throwing made possible a more subtle art. The wheel head was a large, thick, circular piece of wood with shallow holes on the upper surface around the periphery of the disc. The potter kept the wheel in motion by inserting a wooden handle into one of the holes and revolving the wheel head on its shaft until the desired speed was reached.

The handwheel is always turned clockwise, and the weight of the large wheel head induces it, after starting, to revolve rapidly for a long period of time. Pieces made on the handwheel have a high degree of accuracy and symmetry because there is no movement of the potter's body while throwing, as is the case with the kick wheel. In the early days of porcelain making in Japan, the Kyoto, Seto, and Nagoya areas used only the handwheel; elsewhere, in the Kutani area and in Arita, the kick wheel was employed. The Japanese-style kick wheel or ke-rokuro was probably invented in China during the early Ming dynasty. Its design is similar in many respects to that of the handwheel, or it may have a wooden tip set in the top, and an iron pipe, like later wheels. The kick wheel is always turned in a counterclockwise direction, and the inevitable motion of the potter's body as they kick the wheel while throwing gives many Japanese pots a casual lack of symmetry which appeals to contemporary Western tastes.

Following the Meji Restoration in 1868, a student of Dr. Wagener went to Germany to learn how to build a downdraft kilin and observed many wheels operated by belts on pulleys from a single shaft. On his return he set up a similar system in the Seto area, using one man to turn the flywheel that drove the shaft and the pulley system. From this beginning the two-man wheel developed.

Today, most potters in Kyoto use electric wheels, though there are many studios that still have a handwheel and a kick wheel. However, it is now difficult to find craftsmen who can make or repair them.

Coil and throw

At Koishibara, Onda, and Tamba, large bowls and jars are first roughly coil-built on the wheel, then shaped by throwing, in what is known as the "coil and throw technique". The preliminary steps are the same as for coil building, after which the rough form is lubricated with slip and shaped between the potter's hands as the wheel revolves. The process dates back 360 years to a Korean technique brought to Japan following Hideyoshi's invasion of Korea.

Tools

Generally fashioned out of fast-growing bamboo or wood, these tools for shaping pottery have a natural feel that is highly appealing. While most are Japanese versions of familiar tools in the West, some are unique Japanese inventions.

- Gyūbera or "cows' tongues" are long sled-shaped bamboo ribs used to compress the bottoms and shape the sides of straight-sided bowls. They are a traditional tool from Arita, Kyushu.

- Marugote are round, shallow clam shell-shaped bamboo ribs used to shape the sides of curved bowls. They can also be used to compress the bottoms of thrown forms.

- Dango, similar to wooden ribs, are leaf-shaped bamboo ribs used to shape and smooth the surfaces of a pot.

- Takebera are bamboo trimming and modeling "knives" available in several different shapes for carving, cleaning up wet pots, cutting, and for producing sgraffito effects.

- Tonbo, "dragonflies", are the functional equivalent of Western calipers with an added feature. Suspended from a takebera or balanced on the rim of a pot, these delicate bamboo tools are used for measuring both the diameter and the depth of thrown forms.

- Yumi are wire and bamboo trimming harps that double as a fluting tool. They are used to cut off uneven or torn rims as well as to facet leather-hard forms.

- Tsurunokubi, "cranes' necks", are s-curved Japanese wooden throwing sticks used to shape the interiors of narrow-necked pieces such as bottles and certain vases.

- Kanna are cutting, carving and incising tools made of iron and used to trim pieces, for carving, sgraffito and for scraping off excess glaze.

- A tsuchikaki is a large looped ribbon tool made of iron that can be used for trimming as well as carving.

- An umakaki is a trimming harp used to level flat, wide surfaces, such as the bottom of a shallow dish or plate.

- Kushi are not strictly throwing tools; these combs are used to score a minimum of two decorative parallel lines on pot surfaces. The largest combs have about 20 teeth.

- A take bon bon is also not a throwing tool, but a Japanese slip-trailer. A take bon bon is a high-capacity bamboo bottle with a spout from which slip and glaze can be poured out in a steady, controlled stream so the potter can "draw" with it.